On January 31, 2020, the United Kingdom (UK) left the European Union (EU), thus regaining its sovereignty. According to the UK’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson, this also involves re-emerging “as a campaigner for global free trade.”

What implications for palm oil and Malaysia are thinkable now?

The current situation

Since Brexit, the UK has retaken an independent seat at the World Trade Organization (WTO), allowing it to engage in bilateral trade negotiations. The proclaimed goal is to have 80% of total UK external trade covered by preferential trade agreements (PTAs) by 2022.

However, to complete Brexit, the EU and the UK have entered a transition period, currently scheduled to end on December 31, 2020. During that time, the UK remains part of the EU Customs Union and Single Market. Therefore, Britain’s international trade in goods and services will continue, de jure, largely unaffected until then.

However, importantly, the UK already can negotiate and ratify its own preferential trade agreements with third countries to then enter into force after the transition period. Thus, now is a crucial moment to explore future trade opportunities for countries like Malaysia and to start shaping the UK’s domestic regulatory framework.

Will Malaysian palm oil exports to the UK increase in the short term?

In 2019, Malaysia’s global palm oil exports amounted to approximately USD 8.9 billion, of which around 15% (i.e., USD 1.3 billion) were destined for the EU, including the UK.

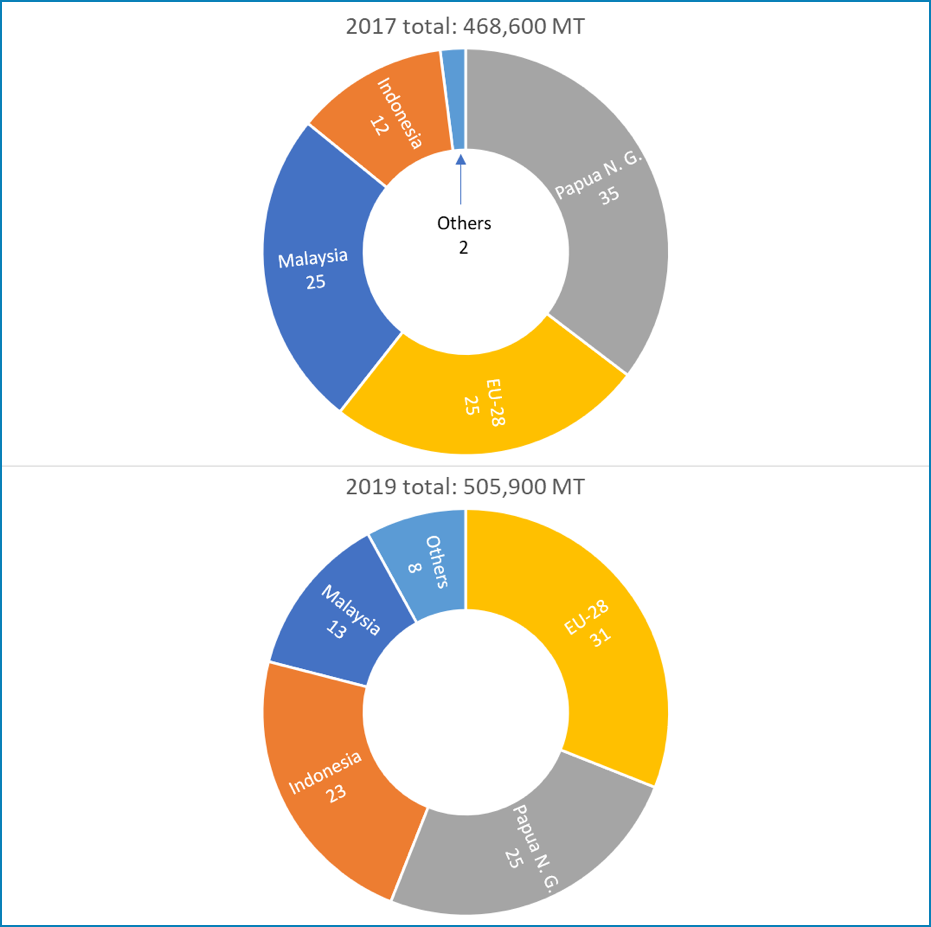

Total palm oil imports by the UK were around 500,000 MT, and Malaysia’s share was 13 % in 2019 (see diagram). Brexit and the UK’s independent trade policy now provide the opportunity to shift trade flows to the benefit of Malaysia and Malaysian palm oil.

Country shares of total UK palm oil imports, in %

Naturally, the overall demand for palm oil hinges on the economic health of the target market. The British economy was in deep trouble well before the Coronavirus hit. GDP growth in 2018 was only 1.3% and 1.4% in 2019, whereas the last quarter of that year registered zero growth.

In light of COVID-19, consultancy firm PwC on April 29 revised its GDP scenario for 2020, expecting a drop of -5% to -10%. The sectors most affected are travel, hospitality, and leisure, with expected declines in output of up to -37%.

Overall, it is difficult to see how a UK-economy grinding to a halt will not affect demand for palm oil negatively. The PwC analysis expects the decline in the sectors most relevant to palm oil to be drastic: food services between -20% to -37%; hotels -18% to 34%; transport -14% to -26%.

However, there may be a silver lining on the horizon. Food and drink retail sales are stable or, in parts, even growing. Fuel demand in the transport sector may also pick up once the worst is over since people shun crowded public transport

Before disaster struck, there were encouraging signs of improvement in bilateral relations. Delegations including UK’s Foreign Secretary Raab and Malaysia’s ex-Foreign Minister Datuk Saifuddin Abdullah met during February 2020 in Malaysia and the UK, stressing “close historical ties and good relationships” between both countries.

The UK, ranking 19th among Malaysia’s biggest trading partners in 2019, has underlined that, in its rapprochement to the Asia-Pacific region, it would seek close alignment with Malaysia. Within ASEAN, Malaysia is the UK’s second most important trading partner by trade volume after Singapore.

Does Brexit provide an opportunity for preferential market access for palm oil?

Malaysia should strive for preferential market access to the UK. Even though under the current EU tariff schedule there are no tariffs on crude palm oil for technical and industrial uses, other palm-based products are subject to duties of up to 12.8 %.

With Brexit and the prospect of an independent UK tariff schedule, these tariffs should be put back on the negotiating table.

The departure of the UK from the EU will also bring up the topic of tariff-rate quotas (TRQs), which determine the quantities of goods that may be imported duty-free or at reduced tariffs (in-quota rates and volumes). Once a quota fills, the regular duty, often significantly higher, applies.

These TRQs are currently being recalculated and reallocated by both the EU and the UK. To date, the EU does not apply any TRQs for palm oil. But given the UK’s future independent trade policy, they should be considered.

Regarding a preferential trade agreement between the UK and Malaysia, Secretary Raab put the focus on a multiparty approach, underlining the UK’s ambition to become part of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP) – a preferential trade agreement between eleven countries in the Asia-Pacific, including Malaysia.

Other possible post-Brexit effects on palm oil

A more favourable view on palm oil?

Following years of intense debate over the environmental impact of palm oil production, the EU has ‘blacklisted’ palm oil as unsustainable in the context of its revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED). It amounts to a de facto ban of the commodity as of 2030.

The RED will no longer bind the UK once Brexit is complete. However, public sentiment against palm oil is strong now (see below) and will not disappear just because the UK leaves the EU. Therefore, Malaysia should not waver in its efforts to produce certified sustainable palm oil and promote it to the British consumer.

Malaysia has already taken the necessary steps by making its Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification scheme mandatory since January 1, 2020. Encouragingly, during his February 2020 visit, UK Foreign Secretary Raab underlined the UK’s will to work proactively with Malaysia to promote biodiversity and prevent deforestation. That may be read as a statement of support regarding Malaysia’s approach to sustainable palm oil.

Better enforcement of labeling rules?

For years now, anti-palm oil campaigns, labeling many food products as ‘palm oil-free,’ have spread throughout the EU. A prominent example in the UK is the case of Iceland Foods Ltd, the country’s leading frozen food retailer. It announced in 2018 to eliminate palm oil in all its own-brand products. The move was accompanied by an anti-palm oil marketing campaign and “no palm oil” labels.

Currently, EU regulations on food labeling, including nutritional information and health claims, apply in the UK. They are implemented, for example, via the UK’s Food Information (England) Regulations 2014 and the Nutrition and Health Claims (England) Regulations 2007.

Brexit may provide a chance to review food laws and make adjustments. Regulation of misleading ‘free from’ claims may receive more attention under the traditionally more market-friendly eye of a post-Brexit Britain.

A chance for the UK, for Malaysia, and palm oil

First and foremost, Brexit should be considered an opportunity. The UK is in the process of mapping out its future trade policy. Also, Brexit allows the UK to draft its own rules, including, for instance, on food labeling. If the Government of Malaysia plays its cards right, the country and its palm oil industry should benefit from Britain’s future.

Prepared by Uthaya Kumar

*Disclaimer: This document has been prepared based on information from sources believed to be reliable but we do not make any representations as to its accuracy. This document is for information only and opinion expressed may be subject to change without notice and we will not accept any responsibility and shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage arising from or in respect of any use or misuse or reliance on the contents. We reserve our right to delete or edit any information on this site at any time at our absolute discretion without giving any prior notice.